Summary

Anointing of the Sick

Anointing of the Sick

The Sacrament of Hope: A Comprehensive Guide to the Anointing of the Sick

In the landscape of human experience, few things are as universal and as unsettling as illness. It confronts us with our own fragility, disrupts our plans, and often brings a crisis of spirit alongside the pain of the body. For two millennia, the Christian tradition has responded to this vulnerability not merely with words of comfort, but with a tangible, sacramental action known as the Anointing of the Sick.

Once shrouded in the somber reputation of being solely a ritual for the dying—historically termed “Extreme Unction”—this sacrament has been restored in the modern era to its biblical roots as a powerful encounter with the Divine Physician. It is a rite of strengthening, forgiveness, and hope, intended for the living who struggle under the weight of serious health challenges.

This comprehensive guide aims to be the definitive resource on the Anointing of the Sick. We will traverse its biblical foundations in the Epistle of James, explore its historical evolution from the early Church through the Council of Trent to Vatican II, and dissect the theological graces it confers. We will examine the liturgical symbols of oil and touch, and distinguish this sacrament from the broader “Last Rites.” This text is optimized for deep understanding, designed to serve students, theologians, caregivers, and those seeking spiritual solace.

Part 1: The Biblical Foundation and Divine Institution

To understand the Anointing of the Sick, one must first look to the ministry of Jesus of Nazareth. The Gospels present Christ not only as a teacher but preeminently as a healer. A vast portion of his public ministry was dedicated to restoring sight to the blind, mobility to the lame, and life to the dying. He touched the leper and the feverish, bridging the gap between the holy and the unclean.

However, the specific institution of this sacrament is most clearly articulated in the apostolic era. The primary proof-text used by theologians for centuries is found in the Epistle of James:

“Is anyone among you sick? Let them call the elders of the church to pray over them and anoint them with oil in the name of the Lord. And the prayer offered in faith will make the sick person well; the Lord will raise them up. If they have sinned, they will be forgiven.” (James 5:14-15)

This passage establishes the essential elements of the rite that persist to this day: The Subject: The one who is sick. The Ministers: The “elders” (presbyters/priests), indicating this is a communal and hierarchical act, not a private one. The Matter: Oil, a substance used in the ancient world for healing wounds and strengthening athletes. The Form: Prayer “in the name of the Lord.” The Effect: A dual restoration of body (“make the sick person well”) and soul (“forgiven”).

Mark 6:13 also provides a glimpse into the early practice, noting that the Twelve Apostles “drove out many demons and anointed many sick people with oil and healed them.” This suggests the practice was instituted by Christ during his lifetime as a means of extending his healing ministry through his disciples.

Part 2: Historical Evolution – From Healing to Death and Back

The trajectory of this sacrament is a fascinating study in theological shifts. In the first millennium of the Church, the anointing was viewed primarily as a rite for the restoration of physical health. It was administered to those who were sick, often repeatedly, with the hope of recovery.

However, during the Middle Ages, a shift occurred. As theology became more systematic, the sacrament became increasingly associated with the final forgiveness of sins before death. It began to be postponed until the very last moments of life, earning the name Extreme Unction (The Last Anointing). It became the sacrament of the dying, a final seal before the soul faced judgment.

The Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) sought to correct this historical drift. The Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy stated, “Extreme Unction, which may also and more fittingly be called ‘anointing of the sick,’ is not a sacrament for those only who are at the point of death.” The Council restored the sacrament to its original intent: a source of strength for the seriously ill, regardless of whether death is imminent. Today, it is celebrated for those undergoing surgery, the elderly, and those with chronic or serious conditions, emphasizing life and grace.

Part 3: The Theology of Redemptive Suffering

The Anointing of the Sick does not promise a magic cure. If it did, no believer would ever die. Instead, it operates on the profound Christian theology of redemptive suffering.

Christianity does not view suffering as useless. It teaches that when suffering is united with the Passion of Christ, it takes on a transformative power. St. Paul writes in Colossians, “I fill up in my flesh what is still lacking in regard to Christ’s afflictions.”

The sacrament gives the sick person the grace to stop viewing their illness as a curse or a punishment. Instead, it empowers them to bear their suffering with patience and courage, offering it for the good of the Church. It prevents the sick person from falling into the despair or self-absorption that often accompanies pain. It reminds the community that the sick are not burdens, but vital members of the Body of Christ who participate in his suffering.

Part 4: The Effects of the Sacrament

The Catechism of the Catholic Church outlines four specific spiritual effects of the Anointing of the Sick, providing a holistic view of how grace operates on the human person.

-

The Gift of the Holy Spirit: The primary grace is one of strengthening, peace, and courage. The Holy Spirit renews trust and faith in God, strengthening the soul against the temptations of the evil one—specifically the temptation to despair or fear death.

-

Union with the Passion of Christ: The sick person is consecrated to bear fruit by configuration to the Savior’s redemptive Passion. Suffering acquires a new meaning; it becomes a participation in the saving work of Jesus.

-

An Ecclesial Grace: By celebrating this sacrament, the Church intercedes for the benefit of the sick person, and the sick person, in turn, contributes to the sanctification of the Church through their faithful endurance.

-

Preparation for the Final Journey: For those who are dying, the sacrament completes the conformity to Christ begun at Baptism. It fortifies the end of earthly life like a solid rampart for the final struggles before entering the Father’s house.

Part 5: The Rite and Liturgy – Symbols of Grace

The celebration of the sacrament is rich in sensory symbolism. It can be celebrated individually (in a hospital or home) or communally (during a Mass).

The Oil of the Sick (Oleum Infirmorum) The physical “matter” of the sacrament is olive oil (or another plant oil in cases of necessity) that is blessed by the Bishop during the Chrism Mass on Holy Thursday. Oil symbolizes healing (soothing wounds), strengthening (gladiators used oil), and light.

The Laying on of Hands Before anointing, the priest lays his hands on the head of the sick person in silence. This is the biblical gesture of invoking the Holy Spirit. It signifies the Church claiming the person for God and the transfer of spiritual power.

The Anointing The essential rite consists of the priest anointing the forehead and hands of the sick person while saying: “Through this holy anointing may the Lord in his love and mercy help you with the grace of the Holy Spirit. May the Lord who frees you from sin save you and raise you up.” The forehead represents the mind and faith; the hands represent human action and agency.

Part 6: Anointing vs. Last Rites

A crucial distinction for digital literacy on this topic is the difference between “Anointing of the Sick” and “Last Rites.” These terms are often used interchangeably by the public, but they mean different things liturgically.

“Last Rites” is an umbrella term referring to the cluster of sacraments and prayers administered to someone actively dying. It typically includes three things:

-

Confession (Sacrament of Reconciliation), if the person is conscious.

-

Anointing of the Sick.

-

Viaticum.

Viaticum is the true sacrament of the dying. It is the reception of the Eucharist (Holy Communion) one final time. The word comes from the Latin meaning “food for the journey.” While Anointing is for the sick, Viaticum is for the departing.

Part 7: Ecumenical Perspectives

While prominently associated with Roman Catholicism, the practice of anointing is found elsewhere. The Eastern Orthodox Church calls it “Holy Unction” or “Euchelion.” It is often celebrated corporately during Holy Week for the physical and spiritual healing of the entire congregation, emphasizing that everyone is spiritually “sick” and in need of healing.

The Anglican/Episcopal tradition and some Lutheran communities also practice anointing of the sick as a sacramental rite, viewing it as a powerful means of grace, though not always classifying it among the “dominical” sacraments (Baptism and Eucharist).

Part 8: Conclusion – The Touch of God

In a sterilized world of medical technology, where death is often hidden and illness is treated as a mechanical failure, the Anointing of the Sick stands as a defiant assertion of human dignity. It declares that the person is more than their diagnosis.

It brings the sacred into the sterile room. It brings the community to the bedside of the lonely. It brings the assurance of forgiveness to the conscience burdened by regret. Whether it leads to a miraculous physical recovery or provides the spiritual fortitude to face death with peace, the sacrament achieves its purpose: it assures the sufferer that they are not abandoned, that they are held in the hands of God, and that in Christ, life—eternal life—is the final word.

The Great Archive of Answers: 4000 Words on Frequently Asked Questions About Anointing of the Sick

To provide the most exhaustive resource available, this section delves into the nuances, the “what-ifs,” and the difficult scenarios surrounding the Anointing of the Sick. We cover the theological, the practical, and the pastoral.

Section 1: Eligibility and Requirements

Q1: Who can receive the Anointing of the Sick? A: This is the most fundamental question. Canon Law (Canon 1004) states that the sacrament is to be administered to a member of the faithful who, having reached the use of reason, begins to be in danger due to sickness or old age. This “danger” does not mean they must be at death’s door. It refers to a significant health crisis. Examples include:

-

A person preparing for a serious surgery (due to a dangerous illness).

-

Elderly people who have become notably weakened, even if no serious illness is present.

-

Sick children who have sufficient use of reason to be strengthened by the sacrament.

-

People suffering from serious mental illness (like severe depression or psychosis) where the illness poses a threat to their well-being. It is not for minor illnesses like a cold, a headache, or a simple broken bone, unless complications arise.

Q2: Can a person with dementia or in a coma receive the sacrament? A: Yes. The Church teaches that the sacrament should be administered to the sick who arguably would have asked for it if they were in control of their faculties. In the case of dementia or a coma, the Church presumes the person, as a baptized Christian, desires the grace of God. The sacrament provides spiritual strength and the forgiveness of sins (even mortal sins) if the person has the internal disposition of contrition but is physically unable to confess verbally.

Q3: Can a non-Catholic receive the Anointing of the Sick from a Catholic priest? A: Generally, Catholic sacraments are reserved for those in full communion with the Catholic Church. However, Canon Law allows for exceptions in cases of “grave necessity” (such as imminent death). If a baptized non-Catholic (Orthodox, Anglican, Protestant) cannot approach a minister of their own community, spontaneously asks for the sacrament, and manifests a “Catholic faith” regarding the sacrament (believing it is a vehicle of grace and forgiveness, not just a symbol), a Catholic priest may administer it. This is a profound act of pastoral mercy at the threshold of life and death.

Q4: At what age can a child be anointed? A: The requirement is the “use of reason.” This is typically defined around the age of 7. However, it is not a strict mathematical rule. If a younger child understands that the priest is praying for them and that God helps them, they can receive it. Infants are generally not anointed because they have not committed personal sins and do not need the strengthening of the will against temptation, as they are already in a state of baptismal innocence.

Q5: Can a person be anointed more than once? A: Yes. Unlike Baptism, Confirmation, and Holy Orders, which leave an indelible mark and are never repeated, Anointing of the Sick can be received multiple times. It can be repeated if:

-

The sick person recovers and then falls ill again.

-

During the course of the same illness, the condition becomes more serious (e.g., a cancer patient whose prognosis worsens or who enters a new phase of treatment). It is not meant to be a daily or weekly ritual (like Communion), but a response to specific crises of health.

Section 2: Theology and Effects

Q6: Does the Anointing of the Sick forgive sins? A: Yes. This is a crucial and often overlooked aspect. James 5:15 explicitly states, “If they have sinned, they will be forgiven.” Normally, the Sacrament of Reconciliation (Confession) is the primary way sins are forgiven. Ideally, a sick person should confess before being anointed. However, if the person is unable to confess (unconscious, intubated, too weak to speak), the Anointing of the Sick grants forgiveness of all sins, including mortal sins, provided the person has “habitual attrition” (a sorrow for sin and a desire for God in their heart, even if they can’t articulate it). This is why only a priest can administer it.

Q7: Does the sacrament guarantee physical healing? A: No. It is not a magic spell. The Church prays for physical healing if it is conducive to the salvation of the soul. Sometimes, physical healing happens. There are countless testimonies of people recovering after anointing. However, the primary healing is spiritual. It heals the wound of fear. It heals the isolation of suffering. It heals the rift between the soul and God. If physical death occurs, the sacrament has still “worked” by preparing the soul for eternal life. The “healing” may be the grace to die well, which is the ultimate healing of the human condition.

Q8: Why is oil used? A: In the ancient Mediterranean world, oil was a staple of life.

-

Medicine: Wine was used to clean wounds, and oil was used to soothe them (as seen in the Good Samaritan story). It represents the soothing of pain.

-

Strength: Wrestlers and soldiers oiled their bodies to make them supple and hard to grip. It represents the strength to fight the spiritual battle against despair.

-

Light: Oil fueled lamps. It represents the light of the Holy Spirit illuminating the darkness of suffering.

-

Spirit: In Scripture, anointing is always associated with the coming of the Spirit (Christ means “The Anointed One”). The oil signifies that the sick person is being conformed to Christ.

Q9: What happens if a person dies before the priest arrives? A: This is a source of great distress for families. If the person is explicitly dead, the priest cannot administer the sacrament. Sacraments are for the living. You cannot anoint a corpse. However, the priest will say specific “Prayers for the Dead” and pray for the absolution of the soul. Furthermore, the exact moment of the separation of the soul from the body is a mystery. If there is any doubt (e.g., moments after clinical death), the priest can administer the sacrament “conditionally” (“Si vivis…” – “If you are living, I anoint you…”).

Q10: Is Anointing of the Sick the same as “Last Rites”? A: Not exactly. “Last Rites” is a colloquial, collective term that refers to the sequence of sacraments given to the dying. Anointing of the Sick is one of those rites. The full sequence of Last Rites for a dying Catholic is:

-

Confession: To clear the soul.

-

Anointing of the Sick: To strengthen the soul.

-

Viaticum: The Eucharist given as food for the journey.

-

The Apostolic Pardon: A special blessing with a plenary indulgence. Anointing can be given to someone who is not dying; Last Rites are specifically for the dying.

Section 3: The Rite and Procedure

Q11: Can a Deacon administer the Anointing of the Sick? A: No. Only a bishop or a priest (presbyter) can administer the sacrament. This is because the sacrament involves the forgiveness of sins, and the authority to forgive sins (Apostolic Succession) is reserved to the priesthood. Deacons can visit the sick, bring Communion, and pray, but they cannot anoint.

Q12: What parts of the body are anointed? A: In the Roman Rite, the priest anoints the forehead and the palms of the hands.

-

Forehead: Symbolizing the mind, thoughts, and faith.

-

Hands: Symbolizing human agency, work, and action. In case of emergency, a single anointing on the forehead or another part of the body is sufficient. In the older form (pre-Vatican II), the eyes, ears, nose, lips, hands, and feet were anointed to purify the senses.

Q13: What if there is no “Oil of the Sick” available? A: Normally, the priest uses oil blessed by the Bishop (Oleum Infirmorum) during Holy Week. However, in a case of true necessity (e.g., a car accident scene), a priest can bless any plant oil (like olive oil or vegetable oil) on the spot and use it for the sacrament. This ensures that the sacrament is never denied due to a lack of specific supplies.

Q14: Can the sacrament be celebrated during Mass? A: Yes, and this is encouraged. Celebrating the sacrament communally during Mass allows the whole parish to pray for the sick. It reminds the community that when one member suffers, all suffer. It removes the stigma of the sacrament being hidden away in a dark bedroom. The sick are brought to the front, often accompanied by family, to be anointed.

Q15: What should a family prepare for the priest’s visit to a home? A: While not strictly required, it is beautiful to prepare a sacred space.

-

A small table with a white cloth.

-

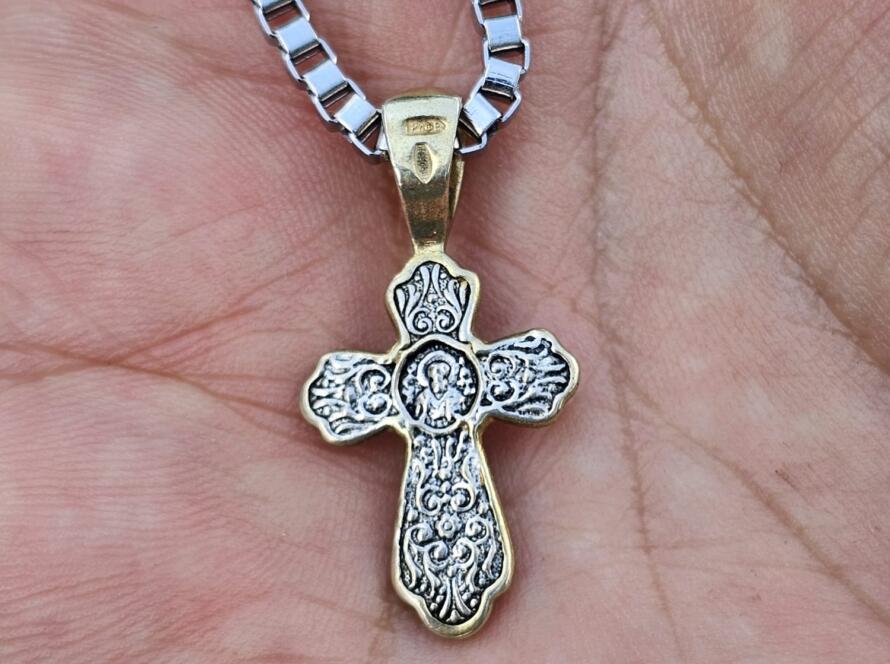

A crucifix.

-

Two lit candles.

-

A small bowl of water (for the priest to wash his fingers after handling the oil).

-

A glass of water (if the sick person needs help swallowing the Eucharist). The family should plan to be present and participate in the prayers, not leave the room (unless the sick person needs to make a private Confession first).

Section 4: Difficult and Sensitive Situations

Q16: Can someone with a mental illness be anointed? A: Yes. The Church recognizes that mental illness is a true sickness that causes immense suffering and can pose a danger to life (e.g., suicide risks, eating disorders). Therefore, someone suffering from severe depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia can receive the sacrament for spiritual strength and healing.

Q17: Can a person preparing for surgery be anointed? A: Yes, if the surgery is caused by a dangerous illness or condition. It is appropriate to be anointed before a major operation (e.g., heart surgery, cancer removal). It is generally not done for minor, cosmetic, or routine procedures where there is no serious danger.

Q18: What is the “Apostolic Pardon”? A: This is a profound and often unknown grace. It is a special blessing given by the priest to a dying person (usually after Anointing and Confession). The prayer is: “By the authority which the Apostolic See has given me, I grant you a full pardon and the remission of all your sins in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.” It grants a Plenary Indulgence, which removes all temporal punishment due to sin. Theologically, this means the soul is prepared to go straight to heaven, bypassing Purgatory.

Q19: Why was the name changed from “Extreme Unction”? A: “Extreme Unction” (Final Anointing) implies that it is only for the very end. This name, popularized in the Middle Ages, caused people to wait too long to call the priest. People were afraid that if they called the priest, they were admitting death was inevitable. The change to “Anointing of the Sick” was a pastoral move to encourage people to call the priest earlier—when the illness begins to be serious—so that the sick person can consciously participate in the prayer and receive the comfort of the sacrament while they are still fighting for life.

Q20: Is the Anointing of the Sick biblical? A: Yes. It is one of the most explicitly biblical sacraments. It is commanded in James 5:14 (“Let him call for the elders…”) and practiced by the Apostles in Mark 6:13 (“They anointed with oil many that were sick and healed them”). It is not a medieval invention; it is a New Testament mandate.

Section 5: Comparative Theology

Q21: How does the Eastern Orthodox practice differ from the Catholic practice? A: Theologically, they are very similar. However, in practice, the Orthodox Church emphasizes the healing aspect even more broadly.

-

Holy Unction services: During Holy Week (Holy Wednesday), the entire congregation is anointed for the healing of soul and body, not just those who are physically ill.

-

Multiple Priests: Ideally, the rite is performed by seven priests (based on the seven prayers), though one is sufficient.

-

Leavened Bread: If Communion is given, it is leavened bread dipped in wine.

Q22: Do Protestants practice anointing? A: Some do, but usually not as a “Sacrament” in the Catholic sense.

-

Anglicans/Episcopalians: Have a rite of “Unction” that is very similar to the Catholic one and is often considered sacramental.

-

Lutherans: Practice anointing as a rite of healing and consolation.

-

Pentecostals/Charismatics: Frequently anoint with oil for healing. They view it as an act of faith and obedience to James 5 to release the power of the Holy Spirit for miraculous healing, but they do not view it as a ritual that forgives sins ex opere operato (by the act itself) in the way Catholics do.

Q23: Why can’t family members apply the oil? A: In the Catholic view, the sacrament is an act of Christ through his Church. The priest acts In Persona Christi Capitis (In the Person of Christ the Head). Just as Christ forgave sins, the priest (his representative) administers the sacrament that forgives sins. A layperson can pray and even use blessed oil as a sacramental (devotional object), but they cannot administer the Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick because they do not have the faculty to absolve sin.

Q24: What if the person is unconscious? A: The sacrament is arguably most comforting in this scenario. The priest can still administer the sacrament. The Church trusts that God knows the heart of the unconscious person. If they would have wanted it, they receive the grace. It provides immense comfort to the family standing by, knowing that the Church has done everything possible to entrust their loved one to God.

Q25: Does the sacrament replace medical treatment? A: Absolutely not. The Catechism and the rite itself are very clear: faith does not replace medicine. We pray for healing and we use doctors. In fact, the book of Sirach (38:4) says, “The Lord created medicines from the earth, and a sensible man will not despise them.” The sacrament is a spiritual remedy that complements medical care; it does not compete with it.

Q26: What is “Viaticum” and why is it important? A: Viaticum is the Eucharist for the dying. It is distinct from Anointing. If Anointing is the medicine, Viaticum is the food. It is the promise of the Resurrection. Jesus said, “Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise them up at the last day” (John 6:54). Receiving Communion on the deathbed is the seal of that promise.

Q27: Can a person be anointed if they have died by suicide? A: Yes. In the past, the Church was more restrictive, but modern psychology and theology recognize that suicide is often the result of severe mental illness that compromises free will. We cannot know the state of the soul at the final moment. The Church prays for all, and the priest will usually administer the sacrament (if they arrive before death) or offer prayers for the dead, entrusting the person to God’s infinite mercy.

Q28: Is there a cost for the sacrament? A: No. It is Simony (a sin) to sell sacraments. A priest will come to the hospital or home for free. However, it is customary (though never required) to give a stipend or donation to the priest or the church for their time and travel, especially if it is in the middle of the night.

Q29: How do I call a priest in an emergency? A: If you are in a hospital, tell the nurse you want a “Catholic Priest.” Most hospitals have a chaplain on call. If not, call the nearest Catholic parish. Most parishes have an “emergency line” on their voicemail specifically for Last Rites. Do not wait until the very last second; call when the situation becomes serious.

Q30: What is the “Grace of the Just”? A: This refers to the state of a soul that is in friendship with God (no unconfessed mortal sin). The Anointing of the Sick increases this grace. It is like polishing a diamond; it makes the soul shine brighter with charity and prepares it to meet God with confidence rather than fear. It transforms the deathbed from a place of defeat into a place of victory.